In the autumn of 2019 CISMAS undertook a refurbishment of the Colossus Historic Shipwreck dive trail.

Condition of the dive trail

The dive trail was heavily covered in marine growth. The exposed wreckage was largely obscured by a bank of detached kelp over a metre deep. All the dive trail markers were heavily weeded, making the station marker numbers illegible. The dive trail sign was obscured by fine seaweed.

Refurbishment

The first task was to remove the build-up of detached kelp stalks. These are often referred to locally as ‘skaffs’ or ‘kelp bombs’. They consist of a loose kelp frond, usually attached to a medium sized rock. These appear to drift onto the site from the west, carried by the flood tide.

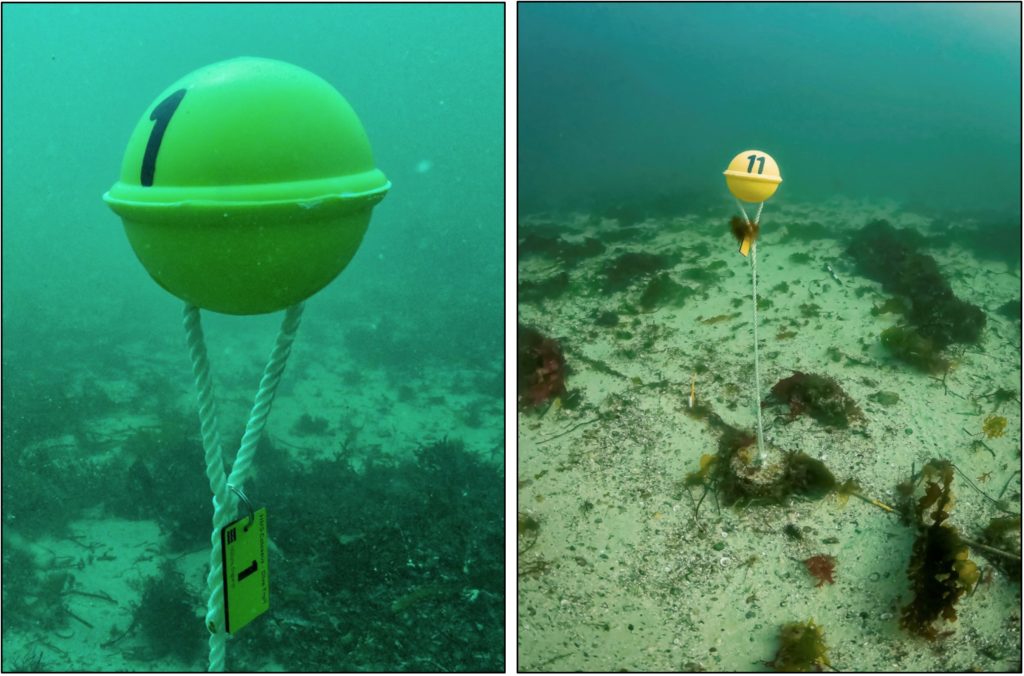

The station marker buoys were then removed and replaced with new marker buoys and ropes. These are fastened to the concrete sinkers on site by passing them through the stainless steel loops which have been cast into the concrete. Small numbered plastic tags have been included beneath the station markers – these have the number etched into the surface and it is hoped they may resist weed growth.

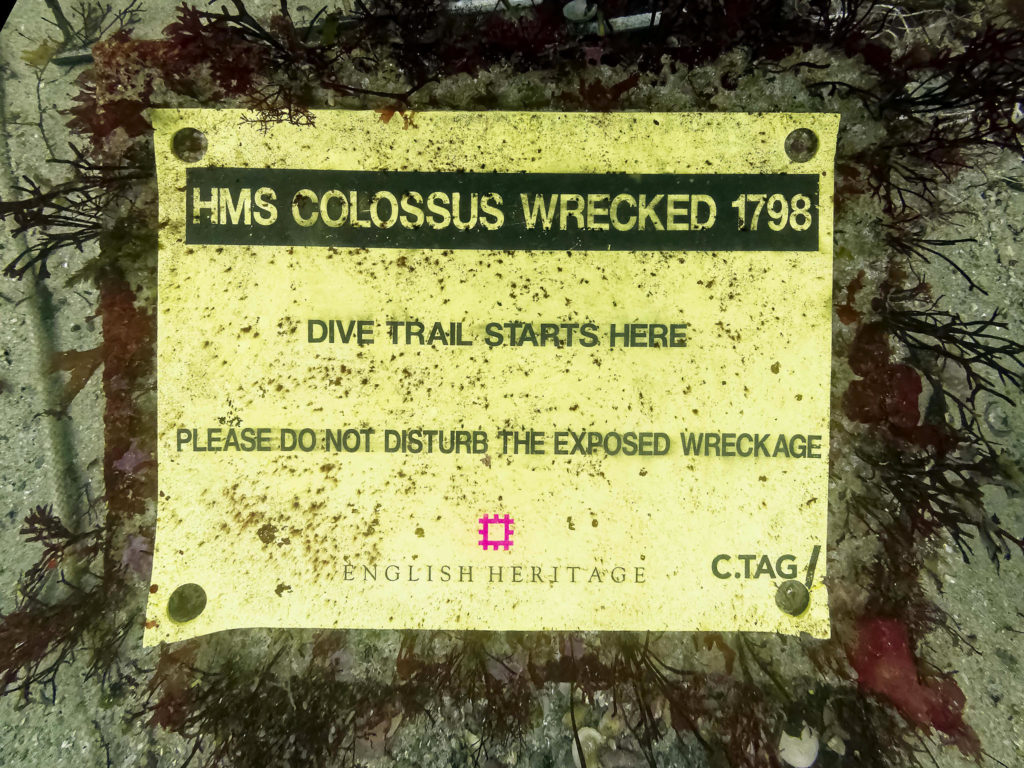

The seabed sign was cleared of the marine growth which was obscuring the sign; this was accomplished using a nylon scouring pad.

The lead-weighted bottom lines which guide divers around parts of the dive trail were checked, de-weeded and renewed where necessary, and additional seabed fastenings installed.

Dive slate

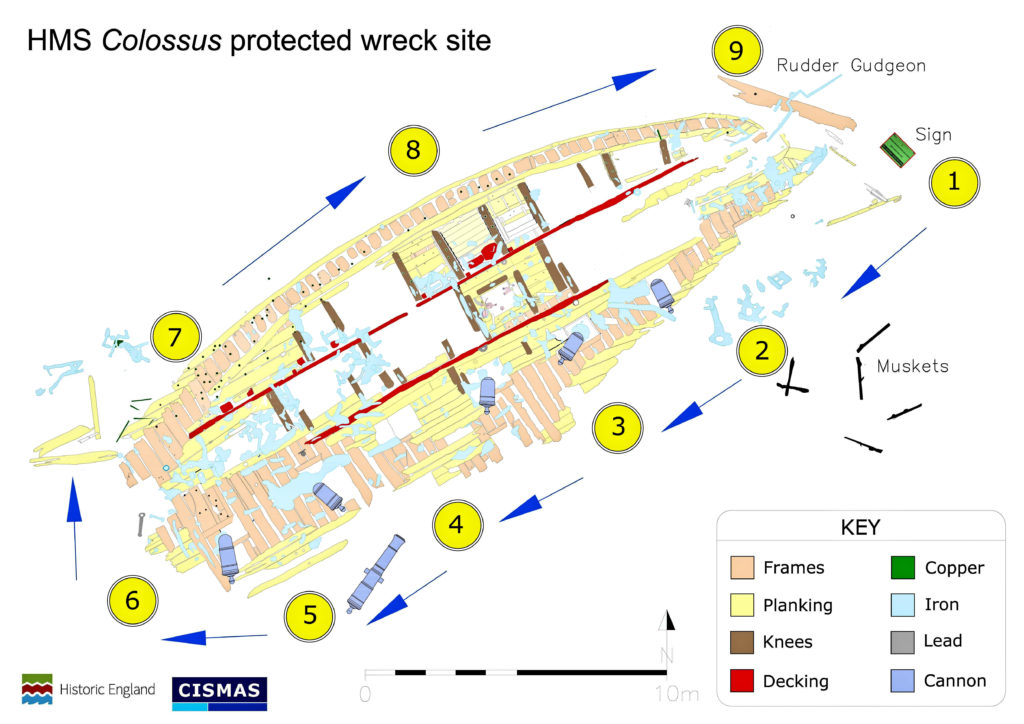

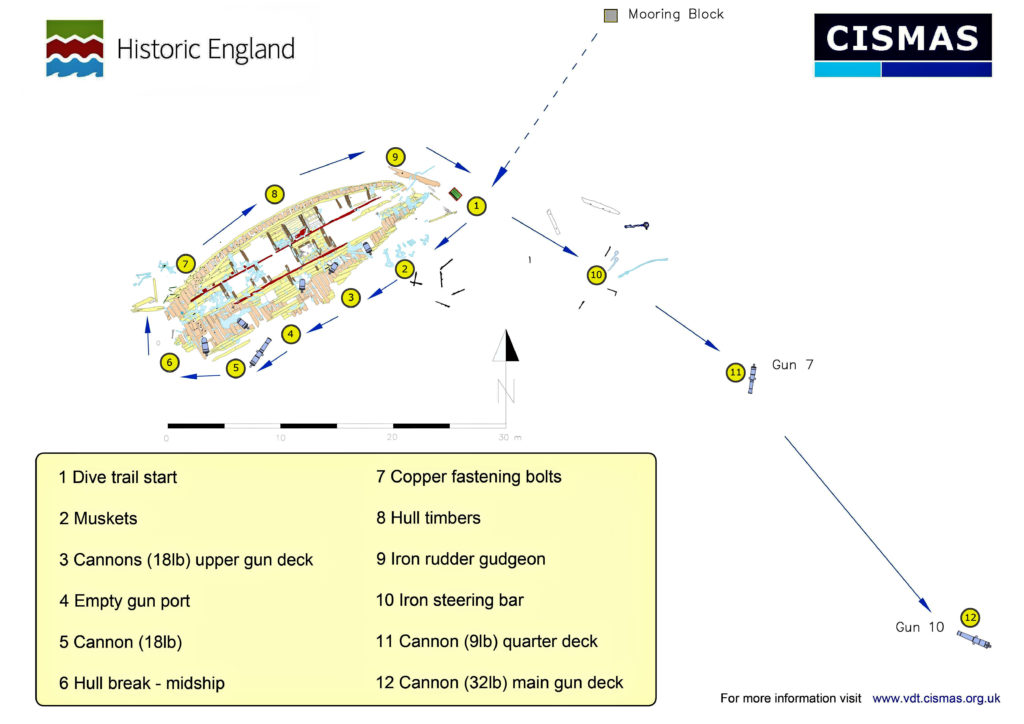

A new underwater information slate was designed. The previous underwater guide was a laminated multi-page guide; these have been in use for over five years and are starting to delaminate. The underwater dive guides are kept on board the dive charter boats in Scilly and loaned to the divers for the duration of their dive on Colossus. Having spoken to a number of these divers and to the diveboat skippers it was decided to replace the multi-page guides with a single A4 dive slate printed on both sides. The new slate is printed onto polycarbonate plastic and should be more durable than the previous, laminated guide booklet. Although the new slate has much less information it is easily portable for the site visit and contains a link to enable visitors to get further information from the online virtual dive trails for Scilly – this is designed to work on a smartphone and also contains information, videos and 3D models for the other protected wreck sites in Scilly.

Note the site plan has been simplified and much small detail removed to make the representation of the site clearer and easier to understand underwater. The dive slate is available to download as a PDF so that independent visiting divers can download and laminate their own information slate.